Let’s face it: I was a weird kid. And few things demonstrate the fact better than a quick survey of my first crushes. The real-life ones were very nice girls (witness the lovely Anna Knott, my girlfriend in second grade), but my choices among crushes in the media were … well … see for yourself.

First and foremost was

Julie Andrews. This is a bit predictable. Conversations with other friends who wound up working in music reveal that we WASPs invariably wound up with crushes on Julie Andrews. My Jewish friends fell for Barbra Streisand. Go figure.

But what was not to love about Julie Andrews? She was English, she was pretty, she sang like a bell, and she performed

magic. Thus I developed crushes on Petula Clark (Irish, pretty, singer) and Elizabeth Montgomery (pretty, magical), because the force of my passion was too much for Julie Andrews to bear alone.

Every little thing she did was magic.

Every little thing she did was magic. Suddenly, going Downtown became my life’s ambition.

Suddenly, going Downtown became my life’s ambition.These thoughts are inspired by the discovery of a long-lost love: Kitirik, the black-cat mascot of Channel 13 in Houston. Her name derived by adding the letter I to the station’s call letters, KTRK, Kitirik hosted a children’s program every afternoon. Like every other kid in Houston, I worshipped her, planned my days around her, and never forgot her. Wouldn’t you know, I found her picture on the Internet. Her real name is Bunny Orsak, and she's still living in Houston. This was the first glimpse I had of her in — well, never mind how many years.

The Divine Kitirik

The Divine KitirikWe must now concede that hers was a daring outfit in Texas, in 1964. From Bunny Orsak to Julie Newmar would be a short step for me. And

Eartha Kitt, too. For a long time, it was all about the Catwomen.

What follows is a gallery of my earliest divas, roadmarkers of a sort along the circuitous route of my boyhood heart.

When you’re a very young kid, it’s not uncommon to fall madly in love with the baby-sitter, which is to say a neighbor who’s not quite grownup, but enough older than you to be fascinating. I adored several women who fit that profile.

Ideal Baby-Sitter I: Lady Betty Aberlin

Ideal Baby-Sitter I: Lady Betty Aberlin

Betty Aberlin pretty much grew up on Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, but from adolescence through thirtysomethingness, she was always charming. Simple, direct, unaffected: she made talking to handpuppets seem natural. She got to sing one of the show’s best songs, “Just for Once,” ostensibly about a child wanting a parent’s attention, but really a poignant love song:

Just for once, just for once,

I want you all to myself

Just for once, let’s be alone...

Absolutely slays me. Years later, Betty Aberlin was nearly cast in Rags, which would have meant my getting to work with her. One more thing to regret about that ill-fated show.

[UPDATE: Not long after I originally posted this, I discovered that Aberlin was Madeline Kahn’s co-star in a satirical revue in the mid-1960s. It’s a measure of her skill and conviction as an actress that I thought she was a kid from Pittsburgh, when in fact she was a Manhattan sophisticate. My interview with Betty Aberlin appears here.]

I also had a serious thing for Judy Graubart, who played Jennifer of the Jungle and other roles on The Electric Company, but I couldn’t find any good pictures of her.

Ideal Baby-Sitter II: Patty Duke as Patty.

Ideal Baby-Sitter II: Patty Duke as Patty.

A hot dog made her lose control, you know.

(I was also fond of the girl who played Cathy.)

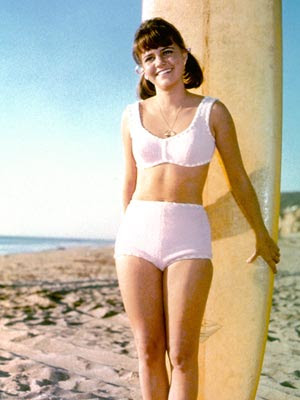

Ideal Baby-Sitter III: Sally Field as Gidget

Ideal Baby-Sitter III: Sally Field as Gidget

Already, I really, really liked her.

Ideal Baby-Sitter IV: Oh, come on.

Ideal Baby-Sitter IV: Oh, come on.

Who didn’t love Hayley Mills?

A kind of transitional figure between baby-sitters and grownups was Marlo Thomas. On That Girl, she played a young woman living on her own — yet under the thumb of her meddling father. I could sympathize with her desire to live independently — even though I had no idea what that entailed. I just wanted to be somebody’s Donald Hollinger.

Diamonds, daisies, snowflakes, etc.

Diamonds, daisies, snowflakes, etc.

Is this the reason I moved to New York?

Then you come to the real grownups, women who are so outright sexy that you have to wonder if Freud was right when he mentions a latency period. Because I wasn’t merely crazy about them. I desired them.

Although for what purpose, I could not have told you.

For example, Shani Wallis, and her cleavage, in Oliver!

Television in the 1960s being what it was, quite a lot of the grownup ladies I craved were the stars of programs that had nothing to do with reality. Besides the aforementioned Julie Newmar, the fantasy realm naturally included Barbara Eden, as well. Somebody once wrote that all history might have changed if Cleopatra’s nose were shorter. I’ve often wondered how history might have changed if we’d ever seen Jeannie’s navel.

Years later, I met Barbara Eden, who talked about Jeannie as a symbol of women’s power, and how it pleased her to hear young women look past the harem pants and see Jeannie as a role-model. All that was beyond me, at the age of seven. The real question was how soon I could visit Cocoa Beach. It was really, really important.

There were some very smart, serious grownup women on TV, too, and I had crushes on several of them.

But what were they telling me? That incredibly beautiful, intelligent women like Barbara Feldon would put up with idiots like Maxwell Smart? I regret to say that very few women possess the infinite patience of Agent 99, and a man can be only a fraction as foolish as Max, before a woman will dump him.

At least I got the message, courtesy of Carolyn Jones as Morticia Addams, that a woman will put up with a great deal of foolishness from a man, so long as he speaks French to her occasionally. It is a message I took to heart, bien évidemment.

Fortunately, Suzanne Pleshette was waiting in the wings, ready to show me that some women won’t put up with any foolishness from a man. Ditto Nichelle Nichols, as Lieutenant Uhura. Why didn’t Uhura ever get to command the Enterprise? Because Captain Kirk was afraid of what she might do to him with a fully loaded phaser bank.

But okay, these are pretty conventional crushes. And I did warn you that I was a weird kid. How weird?

I wanted Veruca Salt NOW!!!

Marcia and Jan Brady? They bored me.

I hungered for Alice.

Whom would you pick, Ginger or Mary Ann?

Mrs. Howell is the one who really sent me.

You can keep Laurie Partridge. I craved Shirley.

(Besides, she did her own singing.)

Watching The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis, you pined for Thalia Menninger (Tuesday Weld). I idolized Zelda.

Watching The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis, you pined for Thalia Menninger (Tuesday Weld). I idolized Zelda.

Sheila James Kuehl, the actress who played Zelda, grew up to be a lawyer and California state senator. And a lesbian. And I still think she’s sexier.

Let’s not even start on Mildred Natwick, Mary Martin, Dame Edith Evans, Ruth McDevitt, Reta Shaw....

Those are better left for another discussion.

With my psychotherapist.

And gosh, I hope my next therapist is as hot as Frances Bavier!

And gosh, I hope my next therapist is as hot as Frances Bavier!

If you ever watched Weber’s engrossing TV series, The Western Tradition, you will know that he not only looked like, he sounded like Harvey Korman, too. You have observed that, if only Tim Conway were around during tapings of Tradition, the sober analyses of history and culture would be interrupted frequently by hysterical fits of giggling. Indeed, that is about the only thing that Weber’s program lacked.

If you ever watched Weber’s engrossing TV series, The Western Tradition, you will know that he not only looked like, he sounded like Harvey Korman, too. You have observed that, if only Tim Conway were around during tapings of Tradition, the sober analyses of history and culture would be interrupted frequently by hysterical fits of giggling. Indeed, that is about the only thing that Weber’s program lacked. If you ever watched Weber’s engrossing TV series, The Western Tradition, you will know that he not only looked like, he sounded like Harvey Korman, too. You have observed that, if only Tim Conway were around during tapings of Tradition, the sober analyses of history and culture would be interrupted frequently by hysterical fits of giggling. Indeed, that is about the only thing that Weber’s program lacked.

If you ever watched Weber’s engrossing TV series, The Western Tradition, you will know that he not only looked like, he sounded like Harvey Korman, too. You have observed that, if only Tim Conway were around during tapings of Tradition, the sober analyses of history and culture would be interrupted frequently by hysterical fits of giggling. Indeed, that is about the only thing that Weber’s program lacked.