My recent rediscovery of James Kirkwood’s Good Times, Bad Times inspired me to seek out another forbidden text from my youth, this one so intimidating that never before ordering it from Amazon had I owned a copy. I used to read it in bookstores, ideally those far from any place where I might be recognized. Gordon Merrick’s The Lord Won’t Mind (1970) held within its pages the potential to undo me — I was certain. But I was quite powerless to resist its spell.

It’s hard to believe that only two years separated the publication of Kirkwood’s novel and Merrick’s, so vast is the difference in their treatment of the stories they tell. Both novels center on pairs of young men of much the same age — on either side of 20 — and of similarly privileged backgrounds and generous endowments. Both narrators begin by telling us they’re motivated by a desire to find “that one special friend,” but only Merrick is honest enough to admit that another kind of desire is at work, too. Whereas Kirkwood’s Peter and Jordan remain purely and improbably platonic, Merrick’s Charlie and Peter are tearing at each other by page 22.

The erotic power that scene held over me, when I was the age of Merrick’s protagonists, can’t be imagined. Not that much imagination was needed: the sex is nothing if not explicit. The scene begins with a corny, drawn-out seduction worthy of the cheesiest porn-movie set-ups — excepting of course that none of those movies had been made when The Lord Won’t Mind was written.

Charlie and Peter’s coupling is quick, ardent, and just the first of many in the book. Kirkwood’s boys share one and only one kiss on New Year’s Eve: two years and a revolution separate these novels.

It may help to think of The Lord Won’t Mind as the gay equivalent of a trashy, Harold Robbins- or Sidney Sheldon-esque story, in which rich, good-looking people get into soap-operatic scrapes and have lots of sex. Of course, most of those novels hadn’t been written yet, either, which may help us to understand how groundbreaking Merrick’s work really was.

According to Wikipedia, where everything is true, Merrick shared a number of traits with Charlie, the older and more experienced (and more profoundly messed-up) of his boys, including a theatrical background and an acquaintance with director–playwright Moss Hart that are reflected in The Lord Won’t Mind. He also had a very long-lasting relationship with another man. Indeed, the book may be viewed as a kind of veiled coming-out story: Merrick’s narrator gives us to understand, at the beginning and the end of the novel, that he and Charlie are one and the same person. At the start, however, he declares that it’s too difficult to tell this story without changing the names and detaching himself from the characters.

So be it: I won’t try too hard to draw biographical allusions. As a document of Merrick’s times, however, The Lord Won’t Mind is especially fascinating. The kinds of incidents Merrick depicts in the book had been going on as long as men have walked the earth, of course, but within his lifetime a new era of openness had begun. Remember, the Stonewall riots took place only one year before this book was published — when it became a New York Times bestseller.*

That success seems improbable to this modern reader, not least because the depiction of sex is, as I say, so far from most mainstream publishing of that era. Really, for equivalents you have to look in the darker corners of pulp fiction, which boasted a considerable subgenre of homoerotic literature set in prisons and reform schools that also seems to have inspired James Kirkwood to at least some degree.

An undercurrent of racism characterizes The Lord Won’t Mind and may account in part for the fact that the book has been out of print ever since Alyson Publications reissued it in 1995. Although Charlie is devoted to Sapphire, his grandmother’s maid (a very marginal character whose tolerant pronouncement gives the book its title), he’s nevertheless inclined to make casual observations that are anything but politically correct. Granted, Merrick is describing pre-World War II New York, when a certain kind of racism was even more widespread, and granted, too, there’s a payoff in the plot twist at the end of the book — but until you get to that point, you may be occasionally uncomfortable in your reading.

Even more pernicious is a broad streak of misogyny throughout the novel. The Lord Won’t Mind features two principal female characters, both of whom start out charming and end up absolute monsters. (I don’t want to spoil the plot, but really, commercial fiction doesn’t get more lurid than this.)

While I’d like to report that more recent generations of gays are entirely reformed and love all women like sisters or goddesses, I do occasionally still hear ugly sentiments expressed. But for the present discussion, what’s most telling is that, in an era when blacks, women, and gays were all fighting for their civil rights, these groups remained largely discrete. Common cause had not been made, and to judge on the basis of the vote in California’s Proposition 8, the struggles aren’t fully united yet, though the goals haven’t been reached.

Charlie’s attitudes toward women also point to his own deeply conflicted character: he’s unable to admit the true nature of his feelings for Peter, and all the plot complications stem from that denial of self. He goes so far as to marry Hattie, an actress who is for several chapters the book’s liveliest and most engaging character. But the constant repression of Charlie’s sexual identity takes its terrible toll on him, on Hattie, and on Peter (who from the first scene freely admits his impassioned love for Charlie), until all three are “acting out” in ways that, even now, are pretty shocking.

That level of psychological insight gives The Lord Won’t Mind whatever enduring literary merit it may have, and again, it points to the revolutionary tenor of the times in which the book was written. To the question “Why can’t you just stay in the closet?” (one that’s still being asked today), the novel offers the clear response: Because bad stuff will happen if I do.

The success of The Lord Won’t Mind inspired Merrick to write several more gay-themed novels, including two sequels in the story of Charlie and Peter. I haven’t read them, and because they’re out of print, they’re collector’s items now, some paperbacks (the Alyson books are rather flimsy) selling for upwards of $100 on Amazon. So I’m not likely to catch up any time soon on Merrick’s work.

He died in 1988, just as writers like David Leavitt were bringing stories of young gay love to a new level, equally open and much better written. The times had been changing, and they continued to change. And for my part, at least I’ve matured to the point where I can own a copy of The Lord Won’t Mind and keep it in my bookcases. My reading is no longer furtive, and I can take the book for what it is — which is not a radioactive scandal waiting to happen.

But page 22 is still pretty darned hot.

*NOTE: A friend tells me that, as a boy, he found Merrick’s novel on the shelves of the public library in the small town in Texas where he grew up. We have deduced that, because the book was a bestseller and because it had “The Lord” in its title, the librarians must have thought it was an appropriate addition to the collections; we can’t believe the librarians ever read it.

It’s hard to believe that only two years separated the publication of Kirkwood’s novel and Merrick’s, so vast is the difference in their treatment of the stories they tell. Both novels center on pairs of young men of much the same age — on either side of 20 — and of similarly privileged backgrounds and generous endowments. Both narrators begin by telling us they’re motivated by a desire to find “that one special friend,” but only Merrick is honest enough to admit that another kind of desire is at work, too. Whereas Kirkwood’s Peter and Jordan remain purely and improbably platonic, Merrick’s Charlie and Peter are tearing at each other by page 22.

The erotic power that scene held over me, when I was the age of Merrick’s protagonists, can’t be imagined. Not that much imagination was needed: the sex is nothing if not explicit. The scene begins with a corny, drawn-out seduction worthy of the cheesiest porn-movie set-ups — excepting of course that none of those movies had been made when The Lord Won’t Mind was written.

Charlie and Peter’s coupling is quick, ardent, and just the first of many in the book. Kirkwood’s boys share one and only one kiss on New Year’s Eve: two years and a revolution separate these novels.

Gordon Merrick: Here he looks much as he describes his characters, cousins who are said to resemble each other strongly.

It may help to think of The Lord Won’t Mind as the gay equivalent of a trashy, Harold Robbins- or Sidney Sheldon-esque story, in which rich, good-looking people get into soap-operatic scrapes and have lots of sex. Of course, most of those novels hadn’t been written yet, either, which may help us to understand how groundbreaking Merrick’s work really was.

According to Wikipedia, where everything is true, Merrick shared a number of traits with Charlie, the older and more experienced (and more profoundly messed-up) of his boys, including a theatrical background and an acquaintance with director–playwright Moss Hart that are reflected in The Lord Won’t Mind. He also had a very long-lasting relationship with another man. Indeed, the book may be viewed as a kind of veiled coming-out story: Merrick’s narrator gives us to understand, at the beginning and the end of the novel, that he and Charlie are one and the same person. At the start, however, he declares that it’s too difficult to tell this story without changing the names and detaching himself from the characters.

So be it: I won’t try too hard to draw biographical allusions. As a document of Merrick’s times, however, The Lord Won’t Mind is especially fascinating. The kinds of incidents Merrick depicts in the book had been going on as long as men have walked the earth, of course, but within his lifetime a new era of openness had begun. Remember, the Stonewall riots took place only one year before this book was published — when it became a New York Times bestseller.*

An early paperback edition

That success seems improbable to this modern reader, not least because the depiction of sex is, as I say, so far from most mainstream publishing of that era. Really, for equivalents you have to look in the darker corners of pulp fiction, which boasted a considerable subgenre of homoerotic literature set in prisons and reform schools that also seems to have inspired James Kirkwood to at least some degree.

An undercurrent of racism characterizes The Lord Won’t Mind and may account in part for the fact that the book has been out of print ever since Alyson Publications reissued it in 1995. Although Charlie is devoted to Sapphire, his grandmother’s maid (a very marginal character whose tolerant pronouncement gives the book its title), he’s nevertheless inclined to make casual observations that are anything but politically correct. Granted, Merrick is describing pre-World War II New York, when a certain kind of racism was even more widespread, and granted, too, there’s a payoff in the plot twist at the end of the book — but until you get to that point, you may be occasionally uncomfortable in your reading.

Even more pernicious is a broad streak of misogyny throughout the novel. The Lord Won’t Mind features two principal female characters, both of whom start out charming and end up absolute monsters. (I don’t want to spoil the plot, but really, commercial fiction doesn’t get more lurid than this.)

While I’d like to report that more recent generations of gays are entirely reformed and love all women like sisters or goddesses, I do occasionally still hear ugly sentiments expressed. But for the present discussion, what’s most telling is that, in an era when blacks, women, and gays were all fighting for their civil rights, these groups remained largely discrete. Common cause had not been made, and to judge on the basis of the vote in California’s Proposition 8, the struggles aren’t fully united yet, though the goals haven’t been reached.

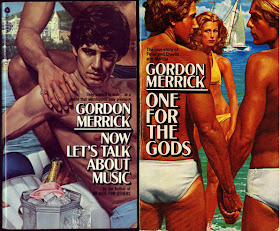

The paperback editions of my youth looked like these.

Charlie’s attitudes toward women also point to his own deeply conflicted character: he’s unable to admit the true nature of his feelings for Peter, and all the plot complications stem from that denial of self. He goes so far as to marry Hattie, an actress who is for several chapters the book’s liveliest and most engaging character. But the constant repression of Charlie’s sexual identity takes its terrible toll on him, on Hattie, and on Peter (who from the first scene freely admits his impassioned love for Charlie), until all three are “acting out” in ways that, even now, are pretty shocking.

That level of psychological insight gives The Lord Won’t Mind whatever enduring literary merit it may have, and again, it points to the revolutionary tenor of the times in which the book was written. To the question “Why can’t you just stay in the closet?” (one that’s still being asked today), the novel offers the clear response: Because bad stuff will happen if I do.

The success of The Lord Won’t Mind inspired Merrick to write several more gay-themed novels, including two sequels in the story of Charlie and Peter. I haven’t read them, and because they’re out of print, they’re collector’s items now, some paperbacks (the Alyson books are rather flimsy) selling for upwards of $100 on Amazon. So I’m not likely to catch up any time soon on Merrick’s work.

He died in 1988, just as writers like David Leavitt were bringing stories of young gay love to a new level, equally open and much better written. The times had been changing, and they continued to change. And for my part, at least I’ve matured to the point where I can own a copy of The Lord Won’t Mind and keep it in my bookcases. My reading is no longer furtive, and I can take the book for what it is — which is not a radioactive scandal waiting to happen.

But page 22 is still pretty darned hot.

I have it on good authority that the characters do not in fact get around to talking about music. One for the Gods is part of the Charlie and Peter trilogy.

*NOTE: A friend tells me that, as a boy, he found Merrick’s novel on the shelves of the public library in the small town in Texas where he grew up. We have deduced that, because the book was a bestseller and because it had “The Lord” in its title, the librarians must have thought it was an appropriate addition to the collections; we can’t believe the librarians ever read it.

Have you ever read anything by Gary Indiana? He is sometimes classified as a gay writer. But his early, out-of-print short story collection, Scar Tissue, establishes that he is a writer, and that noun overshadows any adjective you might put in front of it. He is brilliant and witty in a way that Oscar Wilde might have been if the latter hung around the New York art world and cafe society of the '70s and '80s.

ReplyDelete-- Rick

I've read some of Indiana's work, but mostly his journalism in the Village Voice; the only fiction I've read is his novelization of the Andrew Cunanan case, which I found unsatisfying. I'll keep an eye out for Scar Tissue.

ReplyDeleteScar Tissue is easy to find at The Strand or online. There are many excellent stories in the collection, including one called "Sodomy" that deals with a couple of gay relationships the narrator had "before the war." Given that the setting of the story is around 1978, and given the subject matter of the story, it's not hard to figure out what "before the war" means.

ReplyDelete-- Rick

Fascinating stuff. I have not read Merrick but I also adored Kirkwood's Good Times Bad Times and sent a copy to my Australian best friend - but of course the boys' relationship in it is essentially fake as Kirkwood does not go all the way with it. Same in his 'PS Your Cat is Dead' where the gay burglar and the narrator have another intense relationship that finally turns physical. Sal Mineo made it into a film too. Kirkwood also wrote the book for A Chorus Line so did rather well ...

ReplyDeleteI also loved James Leo Herlihy, best known for writing Midnight Cowboy, I also loved his early novel All Fall Down (filmed perfectly by Frankenheimer with a great cast in 1962) - I was 16 when I read that and I identified totally with Clint, our teenage narrator - Brandon De Wilde was ideal in the film as were Lansbury and Malden as the parents, the young Beatty as the idolised other brother (who of course turns out to be a prize heel) and Eva Marie Saint as Echo O'Brien "the old maid from Toledo". Herlihy also acted, and finally commited suicide.

Merrick's books though were very popular as were Patrica Nell Warren's like 'The Front Runner' which supposedly Paul Newman was going to star in ...

Thanks for writing, Michael. The Front Runner is another of those books I keep meaning to look at but have never read. (Like you, I remember hearing that Newman wanted to adapt the story.) Maybe I'll have to seek out Herlihy's work, too.

ReplyDeleteBrandon De Wilde probably deserves some sort of permanent shrine: he's idolized by legions of men, though of course as time goes by there's every chance that younger generations won't have any idea who he was.

Pulp is pulp. I'm the first to admit that reading Remembrance of Things Past furtively when I was 19 in order to find out what gay guys did in bed was a mistake (10,000 madeleines too late!), but really, The Lord Won't Mind is trash. So were Patricia Nell Warren's books, though when I saw The Fancy Dancer in the hands of a guy on a "Grey Rabbit" hippie bus traveling across the country, I said, "Is that any better than her previous book?" and the guy said something or other, but later that night, when everyone else on the bus was asleep and we were sort of pretending to be ...

ReplyDeleteNo; you can find QUALITY early gay erotica! Yessss! Vincent Virga's Gaywick, e.g., the first all-male gothic (Vincent peddled it to 18 publishers who scoffed that gay readers didn't want "romance," they wanted sex, before Ace took a chance on him ... and promptly sold 180,000 copies), or Mary Renault's The Charioteer (set in World War II) and The Last of the Wine (set during the Peloponnesian War), metaphorical on the sex end but utterly romantic, or The Story of Harold (for LOTS of sex plus storytelling), or many of James Purdy's novels (Eustace Chisholm and the Works, or I Am Elijah Thrush, or Narrow Rooms, or In a Shallow Grave - perhaps the most erotic novel I've ever read), and you STILL haven't broached the eighties yet.

Why settle?

Mary Renault! When I was young in the 60s one had to read her "The Charioteer" and "The Last of the Wine". I particularly liked her later books on Alexander "Fire From Heaven" and "The Persian Boy", which were achingly romantic and had a smidgin of sex too - followed by "Funeral Games". If only Oliver Stone's "Alexander" had followed Renault's stories instead ...

ReplyDeleteMichael O'Sullivan, you're not the first person I've heard to regret that Oliver Stone didn't use Mary Renault's Alexander stories as a guide. My friend Feldstein worships at Renault's temple; in his boyhood, her stories were a hopeful model of possibility, and no matter how much I read them now, I'll never catch up with him.

ReplyDeleteI'm not much of a fan of Stone's work, no matter where he draws his inspiration. The man makes movies with a sledgehammer.

Please, any attribution on the book as to who did the cover illustrations? It came up in of another discussion group. Thanks.

ReplyDeletebtw, Thanks for the great memories, Now, Let's Talk of Music was my first, furtively read, late at night in 1977, when I was 17.

Strangely, blogger is resisting my attempts to leave comments on my own blog. Curious. But we'll try it again --

ReplyDeleteI'm very glad to hear from you. I probably don't have an answer to your question, though I note that the essay features pictures with cover art by three different artists. (Only one is a book I actually possess; the other pictures came from the Internet.) Which one were you talking about?