After a brief pause, Madeleine resumes her journal — and I resume my translating.

MADELEINE’S JOURNAL

NINETEENTH ENTRY

In the country, it’s necessary to rise early. — Preserving sorrel. — Preserving eggs. — Cornichons in vinegar. — Goose preserved in its own fat.

MADELEINE’S JOURNAL

NINETEENTH ENTRY

In the country, it’s necessary to rise early. — Preserving sorrel. — Preserving eggs. — Cornichons in vinegar. — Goose preserved in its own fat.

One fine morning, about fifteen days after my arrival in Valfleury, Tante Victoire awoke me at the break of day.

“Quickly, quickly,” she said. “The weather is lovely, yesterday’s rainstorm has washed the herbs in the garden, we must gather our provision of sorrel and begin our preserves.” [The lexicon at the back of the book defines “preserves” (French: conserves, often used in the singular) as “cooked or raw alimentary substances preserved in jars or cans and hermetically sealed.”]

It was true! I had forgotten that for the past five or six days we had been awaiting a day of nice weather in order to gather the sorrel and to make the winter provisions. I dressed myself without delay and I went down into the garden to do my little harvesting.

_-_The_Young_Shepherdess_(1885).jpg)

The weather was magnificent. Everywhere a delicious odor made of the scent of plants and of the perfume of flowers; a healthy odor of lavender, of thyme, of laurel, with which was mixed the delicate aroma of roses and of heliotropes, Tante Victoire’s preferred flowers.

How nice it was! I didn’t regret rising at the same time as the sun! And to think that at home I have to grab myself by the ear in order to be on my feet at 6:30 or 7 o’clock.

I set about to work, plucking the sorrel leaf by leaf, astonished that it was so tender, and that there was not the slightest leaf wilted. I asked Tante Victoire the reason for this.

“I took the precaution,” she answered me, “to cut the sorrel to the base at the end of the month of August, that is to say, a month ago, and that is why everything we have here is young and tender, it’s always necessary to proceed this way when one wishes to obtain good sorrel for preserving.”

“I took the precaution,” she answered me, “to cut the sorrel to the base at the end of the month of August, that is to say, a month ago, and that is why everything we have here is young and tender, it’s always necessary to proceed this way when one wishes to obtain good sorrel for preserving.”Our baskets being filled, we returned to the kitchen where we brought our harvest. The contents of our baskets were spilled on the table before which I sat, so that I could prepare the sorrel for washing. I took the leaves one by one, I broke off the stem of each, which is always a bit tough, and I threw them into a big bowl of water. They were thus cleaned, then washed several times in cold water.

Tante Victoire then put the sorrel in a kettle, with very little water over a very high flame. The sorrel softened immediately and diminished in volume. Then we removed it from the kettle with the help of a skimmer, and we placed it on a mat where it drained. When it was thoroughly drained, we returned it to the kettle without adding any water (since the sorrel still contained enough of it) and we let it cook over a low flame while stirring it often, so that it wouldn’t stick.

Madeleine seems positively obsessed with sorrel.

Madeleine seems positively obsessed with sorrel.Americans are probably more familiar with Sorrell.

(By coincidence, Buddy’s wife’s name is Pickles, another subject of today’s lesson.)

When it had reached the consistency of a thick porridge, we poured it into earthenware pots, where it cooled. Once it was completely cold, Tante Victoire poured some melted butter over it.

“Why this last step?” I said to Tante Victoire.

“My dear child,” she said to me, that which spoils things is contact with the air. The butter that I am pouring here is going to cool in its turn, forming on top of the sorrel a thick coating through which the air will not pass, and the sorrel will be preserved.

“Tomorrow we shall busy ourselves with a small provision of eggs, to preserve them; you will see that we shall take analogous precautions.”

_-_The_Goose_Girl_(1891).jpg) There was nothing left for us but to seal the pots, which we did with the use of very sturdy paper.

There was nothing left for us but to seal the pots, which we did with the use of very sturdy paper.“There, that is finished,” said Tante Victoire. “You will notice, Madeleine, that I used very small pots for this preserve, since it is necessary, as much as possible, not to keep too long a pot that has been opened. Eight days, fifteen days at the most are enough to make bitter the sorrel that remains in the pots, and it becomes unusable.”

“That is a very good precaution,” I said, “and I shall remember it.”

The next day, as Tante Victoire had said, we busied ourselves with the eggs. For eight days, the hens had furnished us a full basket, which we had not even touched.

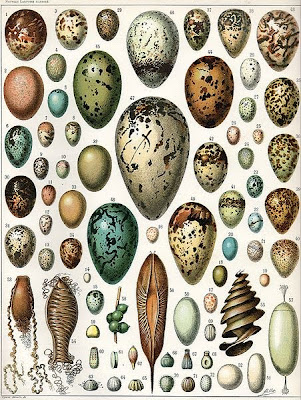

We took the eggs one by one and we wrapped them each separately in a piece of fairly fine paper. Then we arranged them in layers in a box that we filled progressively with wood cinders, taking good care to fill all the empty spaces. The case being full, without our being able to see any bit of paper, it was shut and placed in a corner of the cellar.

We took the eggs one by one and we wrapped them each separately in a piece of fairly fine paper. Then we arranged them in layers in a box that we filled progressively with wood cinders, taking good care to fill all the empty spaces. The case being full, without our being able to see any bit of paper, it was shut and placed in a corner of the cellar.Tante Victoire told me that one could also preserve eggs by using bran instead of cinders; or else by coating each egg with wax, or in letting them soak in great bowls of hot water.*

“You see that, in reality,” Tante Victoire said to me, “what one wants above all in using these diverse means is to protect the eggs from the air, as I explained to you when we preserved our sorrel.:

The whole week passed thus in making different preserves. I am going to write down here the manner in which we preserved cornichons in vinegar.

Remove the stem of the cornichons, wipe them with a rough cloth, place them in a bowl and cover them with coarse salt. When they have remained this way for twenty-four hours, drain them, place them in large, wide-mouthed jars or in earthenware pots, adding peppercorns, one or two cloves, some thyme, some bay leaf, some tarragon, and pour over this some cold vinegar, until they are covered.

Remove the stem of the cornichons, wipe them with a rough cloth, place them in a bowl and cover them with coarse salt. When they have remained this way for twenty-four hours, drain them, place them in large, wide-mouthed jars or in earthenware pots, adding peppercorns, one or two cloves, some thyme, some bay leaf, some tarragon, and pour over this some cold vinegar, until they are covered.Some people, Tante Victoire has told me, stop there, others remove the cornichons from the vinegar after three days, then boil them an instant in new vinegar. Only then do they hermetically seal the container, not to reopen it until the cornichons are good, that is to say eight or fifteen days later.

But the biggest job was the preparation of the confit.

.jpg) Tante Victoire kept in the country a few beautiful geese, all of which she couldn’t have eaten up before our return to town. So she thought of preserving them and of making of them what we call confit. This is the flesh of goose, of duck, or of pork preserved in fat.

Tante Victoire kept in the country a few beautiful geese, all of which she couldn’t have eaten up before our return to town. So she thought of preserving them and of making of them what we call confit. This is the flesh of goose, of duck, or of pork preserved in fat.The geese having been killed, plucked, cleaned, we left them three days without cutting them up.

“Why?” said I to Tante Victoire.

“Because the flesh of geese freshly killed is so fatty and so tender that it’s difficult to cut with a knife. On the contrary, if one lets them wait two or three days, they dry out, firm up again, then one can easily remove the wings and their white meat, and the thighs, without ruining the sinews of the carcass.”

This is just what Tante Victoire did. She cut up the four members of the goose, removed the fat which was found upon the rest of the body and set it aside. Then she seasoned the wings and the thighs with salt, pepper, thyme, and chopped bay leaf, she placed them in earthenware pots, in such a manner that there was no empty space between the pieces. The meat remained in this salting then for twenty to thirty hours.

During this time, we prepared the fat destined to cover the meat. We melted the goose fat in a kettle over a low flame, with a few pieces of bacon and a bit of water. Next, we removed from the salting the members of the geese, we wiped them off and we placed them in this melted fat where they cooked slowly.

During this time, we prepared the fat destined to cover the meat. We melted the goose fat in a kettle over a low flame, with a few pieces of bacon and a bit of water. Next, we removed from the salting the members of the geese, we wiped them off and we placed them in this melted fat where they cooked slowly.“And how shall we know when they are cooked enough?” I asked of Tante Victoire.

“We shall thrust into it this fork, the tines of which are slender and pointed. If the fork passes easily through the confit, that one is cooked enough.”

The experiment having succeeded, the confit was removed and placed again in some pots. Into these pots, we poured the fat in which the confit had cooked, but we waited for that to cool a bit. The pots were then deposed in a corner of the kitchen until the end of the week, after which, the fat being perfectly fixed, we covered them with paper, and we carried them to the cellar.

One thing however intrigued me: how would one eat the goose members thus preserved? I questioned Tante Victoire about this, and she answered me:

One thing however intrigued me: how would one eat the goose members thus preserved? I questioned Tante Victoire about this, and she answered me:“You will come to lunch with me one day next winter, and you will see.”

“But, Aunt, I would really like not to wait until that moment in order to find out.”

“Perhaps you are right,” said Tante Victoire, smiling. “Don’t put off to be learned tomorrow that which we can find out the same day. Here then is how I will use my goose quarters, as folks here say:

“I shall thrust a long fork into the pot, I shall remove from it a piece which I shall ‘brown’ in a frying pan. I shall serve it dry [i.e., without a sauce], or of course with a purée of sorrel or of potatoes. Sometimes I place a goose quarter in the cabbage soup, which makes a delicious broth.”

“But,” said I, “when you remove a goose thigh, for example, from the pot where it is placed, do you not risk uncovering the other pieces?”

“But,” said I, “when you remove a goose thigh, for example, from the pot where it is placed, do you not risk uncovering the other pieces?”“Quite right,” said Tante Victoire, “and so I take care to remove a good piece of fat from the pot, to melt it and to pour it over the place from which the piece was removed.”

“And when there remains no more confit in the pots, what does one do with the fat?”

“One uses it for cooking, instead of butter, and I assure you that it is delicious.”**

What a busy week! … Truly, Tante Victoire was right: I am not wasting my time in Valfleury and I am learning many useful things.

A sorrel omelette in the making.

A sorrel omelette in the making.This appetizing illustration accompanies the Wikipedia entry on “omelette.”

WHAT I MUST DO

[To copy and to keep]

1. Whenever I serve eggs to people in delicate health, I shall give them œufs à la coque instead of hardboiled eggs, these being heavy to the digestion.

2. I shall remember that œufs à la coque must be cooked twice:

First time: one minute and a half in boiling water, on the fire.

Second time: one minute and a half in this same water, off the fire.

3. I shall remember that an omelette is not properly cooked unless it remains soft and juicy.

4. When I am in the country, I shall observe the good habit of rising early.

5. I shall remember that sorrel good for preserving must be young and tender, otherwise it will have a bitter, too-sour taste.

6. I shall not forget that, in order to preserve vegetables, eggs, or meats for a long time, it is necessary to protect them from contact with the air.

7. I shall place in pots smaller rather than large those foods that I wish to preserve, so that they do not risk remaining too long once they have been opened.

8. To preserve sorrel, I shall cook it and I shall place it in pots, covered with a layer of melted butter.

9. To preserve eggs, I shall wrap them one by one in paper, then I will bury them in cinders or in bran.

10. To preserve the meat of goose, of turkey, of duck, of pork, I shall cook it in fat, I shall place it in pots and I shall pour over it the cooking fat that has cooled a bit.

11. To preserve cornichons, I shall wipe them with care, I shall keep them in a bowl under salt for twenty-four hours, then I shall remove them from there in order to put them in vinegar with other condiments.

12. I shall not put off to be learned tomorrow that which I can find out the same day.

Next time: Madeleine learns how to polish copper, wrought-iron, and tin pots. (Oh, and there are some tips on preparing fish, too.)

125. Eggs constitute an excellent food, nourishing and light at the same time. They are suitable to everyone, but particularly to delicate stomachs.

126. There is a very great number of methods for preparing eggs. The most ordinary are:

Œufs à la coque.

Hard-boiled eggs.

Fried eggs.

Eggs in an omelette.

127. Œufs à la coque. — Plunge them into the water while it is boiling. Leave them on the fire for one minute and a half. Remove the saucepan and leave them in the water, off the fire, for another minute and a half. This second part of the operation permits the eggs to make their milk, that is to say that the egg white, instead of hardening, remains liquid and takes on the appearance of milk.

128. Hard-boiled eggs. — To harden eggs, leave them five minutes in boiling water. Then remove them, remove the shell and cut each egg in two or in four pieces. Cut this way, the eggs are arranged upon a purée of sorrel or added to a lettuce salad, etc.

129. Fried eggs. — Put butter in a dish on the fire; let it melt without browning, gently break the eggs, arranging them next to each other while taking care not to break the yolk. Salt,*** let cook over low flame, and remove from the fire when the albumen is cooked everywhere, without its becoming hard.

130. Eggs in an omelette. — To make an omelette, break some eggs in a bowl, white and yolk together.

Elsewhere, one has placed on the fire a good piece of butter in a skillet. While it melts, beat the eggs with a fork, without forgetting to salt them with fine salt.**** The butter being hot without browning, pour into the skillet the beaten eggs. Let them “set,” then, from place to place one raises the omelette a bit to avoid its sticking to the skillet and to let the butter circulate everywhere.

When the omelette is cooked enough, that is to say when the egg is half-liquid, tilt the skillet obliquely. The omelette should slide to the edge of the skillet and there, with the tip of a fork, one folds it in two, in a single gesture. Then place it on a long dish.

131. In order to vary omelettes, one varies the elements that one incorporates with the eggs. Sometimes these are chopped fines herbes that one adds to the eggs before beating them, sometimes mushrooms cut into small pieces that one cooks for an instant in the skillet, sometimes small pieces of bacon, sometimes fried croûtons, sometimes jam that one adds just before folding the omelette.

*TRANSLATOR’S NOTE: Anybody want to try this at home and let the rest of us know how it turns out? I confess I’m not brave enough.

**Oh, is she right about that!

***Sacré bleu! Jacques Pépin says that salting eggs while cooking them is a sure-fire way to end up with tough eggs. Jacques advises us to wait until the eggs are ready to serve before salting them — my egg dishes have been notably tastier ever since.

****Again with the salt! Beyond that disputable instruction, this is one of the more inscrutable descriptions of omelette-making I’ve ever encountered.

No comments:

Post a Comment